Following the announcement of rising crime statistics on Tuesday, the Cape Flats community is planning a mass shutdown at the beginning of October to demand an end to gang violence.

Crime is an ongoing problem in the Cape Flats.

With South Africa holding a reputation for regular protest action, community members have been taking to the streets long before the announcement.

Busisiwe Zasekhaya, coordinator at the Right2Protest Project, explains that it’s important to understand that protests do not just happen overnight.

She says that after following the correct procedures and trying to engage authorities for several years, protests are often the last resort.

Community members from the Cape Flats have made headlines on several occasions trying to combat the violence they are exposed to daily.

According to Dr Carin Runciman, associate professor at the Centre for Social Change at the University of Johannesburg, protests mostly concentrate around issues of service delivery.

However, she points out that a significant proportion of protests also raise issues about the quality of governance, such as complaints about corruption and municipal dysfunction.

“This is clearly a response to the perpetual instability of local government, which is structurally unable to provide for the needs of the people,” says Runciman.

Despite the police implementing Operation Thunder on the Cape Flats, which led to 11,000 arrests and the confiscation of 130 firearms, recorded murders have risen by 7% nationwide.

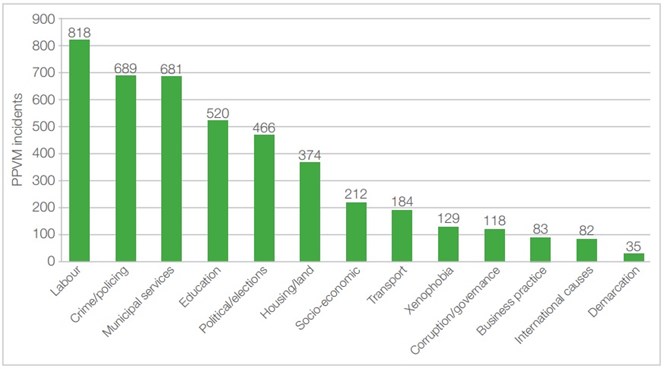

According to the South African Crime Quarterly, which was released in June 2018, crime and policing was cited as the second most popular reason to protest between 2013 and 2017.

The below graph outlines this, as well as other types of grievances that were reported as a reason for protest, such as municipal services and education:

What is the State of Protest in South Africa?

Zasekhaya emphasises that the right to protest is one which is afforded by the Constitution of our country, and that the number of protests is reflective of our societal issues.

The Right2Protest Project, an organisation which offers support to protestors nationwide, released a report on the State of Protest in SA from October 2016 to September 2017.

It looks at the main barriers to protest during this period. Zasekhaya outlines the main observations made in the report below:

- Authorities in municipalities often misapply the RGA and there is a lack of consistency regarding its application. One municipality may require protesters to pay a fee to protest, while another may require written confirmation from the entity that communities are protesting against in order to approve the protest. Failure to produce written confirmation often means that your protest will be prohibited.

- There is an increase in the use of interdicts to prohibit protests. These interdicts are often quite broad, and this trend is seen specifically in mining communities.

- The use of force during protests is often not proportional to the threat posed.

- Protesters have reported intimidation by police as an attempt to stop them from engaging in further protest action.

What about violent protests?

Zasekhaya says there has been a mischaracterisation of violence in protest action in South Africa.

“Violence by the police is often not covered in our media, and the disproportionate use of force is hardly ever addressed,” says Zasekhaya.

Therefore, when addressing the issue of violence, she believes it is important to take note of that narrative and how the label of violent protests may be used to discredit protesters.

Runciman agrees that when violence is reported it often focuses on the actions of protestors rather than police action.

She believes it is important to consider the definition of violence. Often the blocking of a road or the burning of a tyre is reported as violent when it may, in fact, only be disruptive.

She adds that the characterisation of such protests as violent often serves to delegitimise the genuine grievances being put forth by protestors.

“When violence from protestors does occur, it is a response to the violence that most ordinary South Africans have to face in their daily lives,” says Runciman.

According to Nompumelelo Kekana, legal assistant at the Freedom of Expression Institute, the police may only use force against protesters in order to prevent injury or death to a person or destruction of property, and only when negotiations and all other measures have failed.

“Before resorting to force, they must give two warnings in at least two languages, and give people reasonable time to disperse,” says Kekana.

“They may only use the minimum possible force. These rules must be adhered to whether or not the protest is perceived to be illegal,” she adds.

Steps to organise a protest

According to Runciman South Africa has amongst the highest rates of per capita protests in the world. This tells us the country is experiencing a crisis in the quality of its post-apartheid democracy.

With so many disgruntled citizens, many may wonder how to organise a legal protest.

Kekana explains that if someone wants to organise a legal protest, they would have to start by informing their local authorities.

This is according to the Regulation of Gatherings Act (RGA), which regulates protest action in South Africa through giving effect to section 17 of the Constitution.

“If you organise a gathering with 16 or more participants, you must first notify the local municipality. If the gathering has 15 participants or less, it is called a demonstration and no notice needs to be given,” says Kekana.

She points out that if notice needs to be given, you must make sure it’s done at least seven calendar days before the protest.

“If you cannot give notice within the seven days, you may give notice in less than seven days, but you must give reasons as to why your notice is late,” says Kekana.

However, if notice is given less than 48 hours before a protest, regardless of having legitimate reasons for it being late, the protest may be banned without cause.

“The notice does not constitute a request for permission to gather. Rather, it exists so that the local authorities can logistically facilitate your gathering,” says Kekana.

“This could include redirecting traffic in affected streets or raising legitimate security concerns at the Section 4 meeting,” she adds.

Within 24 hours of giving notice to your local authority, you will be invited to a Section 4 meeting, where the relevant authorities will discuss the logistics of the gathering.

If you are not contacted for the Section 4 meeting, then your protest is automatically considered legal and you can continue as planned.